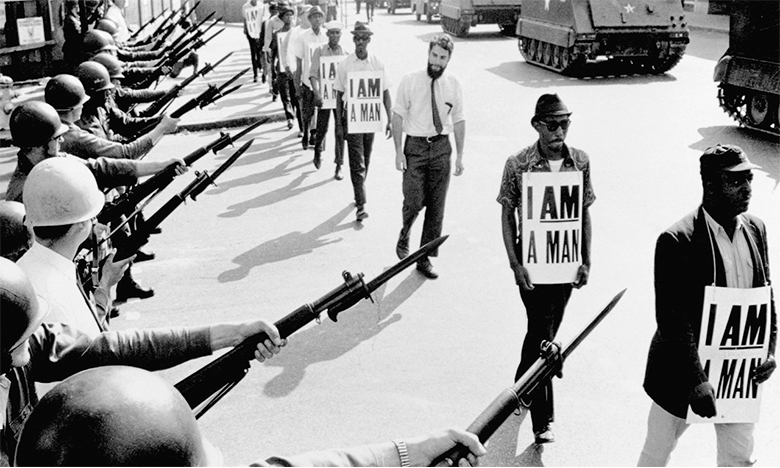

Conditions for the city’s Black sanitation workers were difficult to the point of deadly. Memphis was paying full-time employees a meager minimum wage, then just $1.60 an hour. But it wasn’t until two men died on the job in February 1968 that protests broke out, with hundreds of sanitation workers taking to the streets to demand their right to unionize.

Most remember the 1968 strike because it drew Martin Luther King Jr. to the hotel balcony where he was assassinated. But the protesters’ picket signs have their own place in history. “I am a man,” the signs said. Not a boy. Not a garbage collector or sanitation worker. A man.