Enough with the buzzers, whistles and horns. American football had no clear way of signaling a penalty, and Dwight “Dike” Beede was fed up with the confusion this caused on the pitch. So in 1941, the Youngstown College coach decided to take his work home with him — where he asked his wife, Irma, to help create something that would end up permanently changing the fabric of the game.

At the time, Beede was 38 years old. Having been the youngest-ever college coach, he would one day become the oldest — a football lifer. He played football for South High School in Youngstown, Ohio, and then went on to Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, facing off with opponents like Notre Dame’s fabled Four Horsemen. He served as coach at Geneva and Westminster colleges in Pennsylvania, before being hired by Youngstown College in 1938.

"I CAME HOME FROM PRACTICE AND ASKED MY WIFE TO DO A LITTLE SEWING."

Player-coaches weren’t unusual in the professional ranks, and full-time college coaches were less common than today. In fact, Beede got paid only $1 a year at Youngstown College and worked full time as an insurance agent.

In the early 1940s, football was vastly different from today’s game. Players wore very little padding and leather helmets with no face masks. The NCAA was formed in 1905 to govern college football; 15 years later, the American Professional Football Association was formed in a Hupmobile dealership in Canton. Two years later, it changed its name to the National Football League.

The goalposts were on the goal line, and until 1941, players were expected to play both offense and defense. The rules on substitution were relaxed that year, as the peacetime draft signed into law a year earlier depleted the numbers of collegiate football teams. And there was no clear way to signal a penalty.

Some officials blew a whistle, but whistles were also used to mark the end of a play, which caused confusion. Some schools had a horn that blew for infractions, which suffered from the same problem — as well as its own drawbacks, like being loud, says Ken Breyer, a former student manager and sports information director at Youngstown State University.

“People in the stands would bring their own horns,” says Breyer, who shared an office with Beede in the 1950s. Sometimes horns and whistles could not be heard above the din of the crowd — or in press boxes, where games were being broadcast on radio.

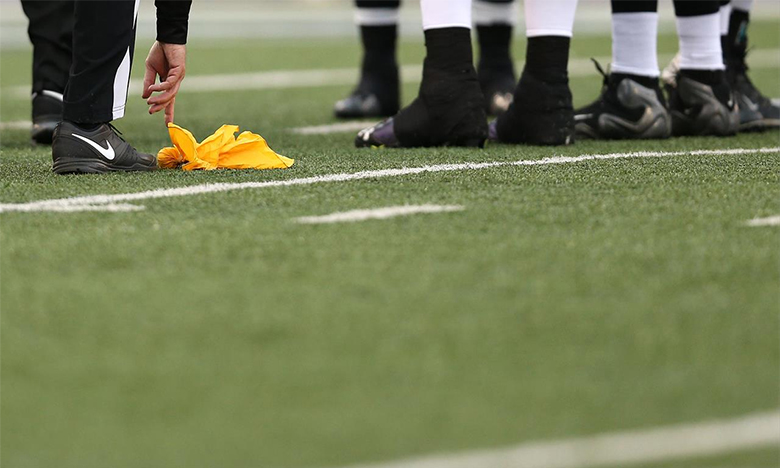

Running drills on the field was one thing, but Beede had a creative solution up his sleeve. He knew that he needed Irma’s know-how, so, as he admitted 28 years later, “I came home from practice and asked my wife to do a little sewing.” Beede wanted a visual signal, so he waved a flag by way of a solution … with Irma’s help. Irma cut up one of their daughters’ Halloween costumes and sewed it together with pieces of bedsheet to make four flags, each 16 inches square. She then added drapery weights, to give them some heft, and, voilà, the first penalty flags were created.

To test the banners, Beede found a willing collaborator in Os Doenges, the coach at Oklahoma City College (now Oklahoma City University). On a Thursday at Rayen High School Stadium — Youngstown’s home field, on the city’s North Side — Beede handed a flag to each of the four men officiating. One of them was Jack McPhee, who had already been part of a groundbreaking college game. In 1939, McPhee officiated the first televised football game, between Fordham and Waynesburg. He liked the flags immediately and found them a great help, so much so that he kept his after that first game — a decisive 48-7 win for Beede’s Penguins — and continued to use it.

In 1943, McPhee became an official with the Western Conference (now the Big Ten), and used the flag at a game between Ohio State University and the University of Iowa. Among the spectators was league commissioner Maj. John Griffith, who was impressed enough that the following week, he decreed referees use flags at all Western Conference games. Cue the era of the penalty flag.

McPhee continued to use the flag sewn by Irma Beede for years, raising it in the Rose Bowl and in Army–Navy and Notre Dame–Southern California clashes. In 1969, he finally retired the flag and donated it to the College Football Hall of Fame. For her role as “the Betsy Ross of Football,” Irma Beede received a commemorative flag, which is on display at Stambaugh Stadium, Youngstown State’s home field since 1982, not far from where the flag was first thrown at Rayen Stadium.

In 1965, 17 years after the penalty flag was officially adopted in the NFL, the league changed the color to yellow, which showed up better on the new color TVs. Nine years later, yellow flags were put to use in college games as well, and a yellow flag remains the standard in American football (the Canadian Football League uses orange).

Breyer says Beede, who died in 1972, just a month after his retirement, never thought of the penalty flag as something that would become so ingrained in the game. “He told me he saw a problem and offered a solution,” Breyer says. “He had no idea how big it would grow.”