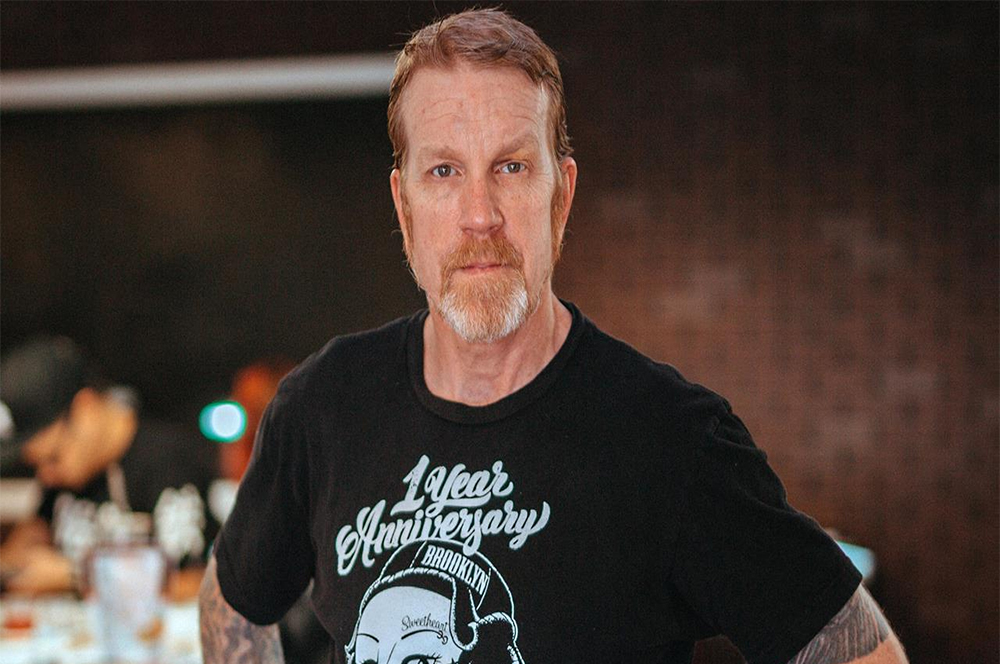

Guy Prandstatter is surprisingly affable for a person who’s managed to piss off so many people. But he’s also unapologetic about why they’re angry. For too long, he believes, anyone wishing to set up as a tattoo artist has had to endure a grueling, unpaid and, he claims, sometimes abusive stint as a shop apprentice. Prandstatter says the process discourages many deserving prospects from breaking into the business and, the way he sees it, makes the tattoo industry ripe for disruption.

That’s why the 53-year-old tattooer and musician from New Jersey is building a network of for-profit schools aimed at training newcomers through what he says is a rigorous and structured program built on proper training. What’s not included? Odd jobs like sweeping floors, cleaning toilets and any number of menial tasks that are typical of a traditional apprenticeship. Upon completing the Academy for Responsible Tattooing (A.R.T.), which takes one to two years on average, graduates are promised a spot at one of Prandstatter’s seven studios from New York to California, which double as school locations.

With more than 100 graduates since first opening its doors in 2011, A.R.T. is growing quickly. It’s also a self-subsistent tattoo ecosystem of sorts: Prandstatter and his business partner, Paul-Anthony Surdi, tap the pool of fresh talent to feed their expanding network of studios. The more students Prandstatter educates, the more employees he can hire at his shops. “There are tens of thousands of people everywhere who have been denied access to the education,” he says. “If there’s a dense enough population, I could build a business anywhere and be successful.”

Today, Prandstatter is a man with a plan, but it wasn’t always that way. The ex-Marine fell into the business in the late 1980s after a chance encounter with a tattooer at the gym. He’s got no horror stories to report — he cleaned his mentor’s car, painted her house and served, he says, as her “personal errand boy” — but looking back, he says he’d have taken the opportunity to study at one of his schools “in a heartbeat.”

"WE MAKE IT LOOK EASY BECAUSE WE’VE BEEN DOING IT SO LONG, AND THEY THINK THAT IT’S EASY."

The problem, according to his critics, is that A.R.T. subverts tattoo tradition by doing away with the time-honored apprenticeship and cycling poorly trained students through the program to make a quick buck. They maintain that the arduous journey from apprentice to artist — a several-years-long trial by fire meant to build discipline and loyalty, both to the mentor and the craft — is what makes a dedicated tattooer. Making needles, building machines and, yes, keeing the shop clean and your mentor happy are all part of the protocol. “No one is willing to do that these days. They watch TV and say, ‘I can do that,’” a Philadelphia-based tattooer known as Eric Perfect posts online. “We make it look easy because we’ve been doing it so long, and they think that it’s easy.”

Around the country, artists like Perfect, who has helped organize an anti-A.R.T. campaign, have spoken out against Prandstatter’s school on social media and even taken to the streets with slogans like “Earned, Not Paid For.” Earlier this year, A.R.T. was forced to abandon plans to open in Oakland, California, after mounting protests there.

regulation or central authority. Besides having to pass a blood-borne pathogens exam, there’s little by way of official oversight in a profession governed mostly by tradition and an unwritten code enforced among peers. It’s also a world, Prandstatter claims, in which wide-eyed, would-be tattooers risk being exploited as free labor. “You could be an apprentice in a shop for two years, busting your ass, and one day come in and the guy says, ‘We don’t want you here anymore — get lost,’” he says. “And you’ve got no recourse. You’ve just got to walk away.”

Critics say highlighting the potential pitfalls of a traditional apprenticeship is Prandstatter’s way of using scare tactics to sell his school. True or not, his training model replaces what would appear to be an uncertain path with guaranteed, full-time employment at one of his shops. And while the school may cost thousands of dollars to attend, it also gives students the chance to study at their own pace while holding on to day jobs. Eric Del Valle, a 33-year-old A.R.T. graduate, says he’d long wanted to tattoo but wasn’t able to commit to a full-time, unpaid apprenticeship. “Why should I be turned off from it just because I don’t have time to do it that way?” he says. “The opportunity should be available to everyone.” Today, Del Valle works for Prandstatter at Body Art and Soul in Brooklyn.

Not everyone shares such positive feedback. One graduate, who insisted on speaking to OZY anonymously for fear of reprisal, reports that students were supervised by minimally trained recent graduates. Some of those teachers were even alleged to have left customers with scars. The source’s account echoes concerns voiced by many tattooers that A.R.T. produces substandard artists who are unprepared, or simply unfit, to work on clients on their own. After spending nearly $10,000 on the school, the source severed ties with A.R.T. after graduating, and then began a traditional apprenticeship.

Prandstatter acknowledges that A.R.T. may not have satisfied everyone’s expectations, but says the program is now “light-years ahead” of where it started. And he remains committed to training the right people — not just anyone who will pay. “I invest in a long-term proposition with people because I’m going to hire them,” he says. Which sounds good for his graduates and good for the “empire” he says they’re building together. But will Prandstatter’s empire be good for the tattoo industry? Depends on which artist you ask.